The Wisdom of the Mystics

Richard Rohr shares how studying the mystics can transform us and help us meet the needs of our times:

We live in a time of both crisis and opportunity. While there are many reasons to be anxious, I still have hope. Westerners, including Christians, are rediscovering the value of nonduality: a way of thinking, acting, reconciling, boundary-crossing, and bridge-building based on inner experience of God and God’s Spirit moving in the world. We’re not throwing out our rational mind, but we’re adding nondual, mystical, contemplative consciousness. When we have both, we’re able to see more broadly, deeply, wisely, and lovingly. We can collaborate on creative solutions to today’s injustices. [1]

Can seeing with the eyes of mystics really have relevance in our busy modern world? I think it is not only relevant but absolutely necessary to change our levels of consciousness, which many religious traditions might have also called growth in holiness or divine union. As Einstein said (though now in my own words), we have tried to solve today’s problems with yesterday’s software—which often caused the problem in the first place. Through a regular practice of contemplation we can awaken to the profound presence of the unitive Spirit, which then gives us the courage and capacity to face the paradox that everything is—ourselves included. Higher levels of consciousness always allow us to include and understand more. Deeper levels of divine union allow us to forgive and show compassion toward more and more, even those we are not naturally attracted to, and even our enemies.

Mystics have plumbed the depths of both suffering and love, and emerged with depths of compassion for the world, and a learned capacity to recognize God within themselves, in others, and in all things. If we can read the mystics with an attitude of simple mindfulness, the insights and practices they share can equip us with a deep and embracing peace, even in the presence of the many kinds of limitation and suffering that life offers us. From such contact with the deep rivers of grace, we can live our lives from a place of nonjudgment, forgiveness, love, and a quiet contentment with the ordinariness of our lives—knowing now that it is not ordinary at all!

By applying the wisdom of the mystics to our daily and even momentary outlooks, we will be able to bring open-heartedness into the lives we lead and the work we do. Then we might just be able to recognize that the ordinary path can also be the way of the mystic. It is all a matter of the eyes and the heart.

Studying the mystics, and hopefully identifying with them in at least some small way, allows us into the seemingly simple yet always profound realm of those who have found their way close to God and all of creation. The path of the mystic is within our reach. [2]

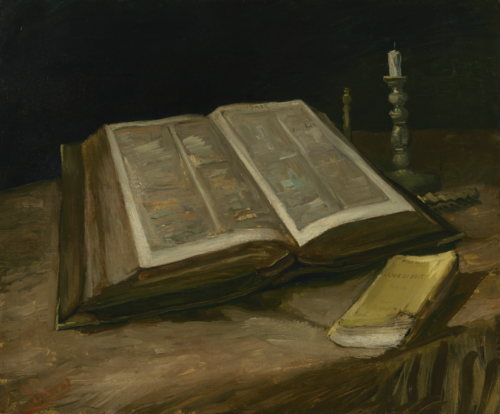

A Single Flame

In his talk Hell, No!, Father Richard considers the image of fire in the Scriptures:

God heals people by making them into what they are really meant to be. The prophet Ezekiel proclaims that when Israel sins, all God does is love them more. Their image for that love was a purifying fire. Often when the word fire is used in the Bible, it’s not a torturing fire, it’s a purifying fire. That’s a metaphor that mystics and poets still use to this day. We describe times of suffering that offer us greater strength, insight, or resilience by saying, “I was tried by fire.”

In one chapter, Ezekiel repeats the word restore. God says to the people, “I will restore them … I will restore them … I will restore you” (see Ezekiel 16:53–56, Jerusalem Bible). The prophet has spent chapters scolding them for their unfaithfulness to their covenant with God, and then he changes course. Ezekiel says that God’s love, forgiveness, and commitment to restorative justice are so complete that Israel’s conscience will awaken. They will understand what they have done and be reduced to silence and confusion (see Ezekiel 16:63). That’s what we Catholics understood as purgatory. Here’s an example: Have you ever spoken ill of somebody, actively disliked somebody, or put someone down in the presence of others? Then they approach you, and it turns out they’re not only nice, but they’re really nice. They wish you well. That feeling is called remorse; we used to call it compunction. We are reduced to silence and confusion. Let’s be honest, grace is always a humiliation for the ego.

Of course, we clergy overplayed the notion of purgatory, making it some kind of retributive justice instead of restorative love. We couldn’t deny the mercy of God, and we knew that the love of God was going to win, but we still made it necessary to burn there for some number of years. We had a deeper intuition of love’s flame, but we settled instead for the literal fire. [1]

Teresa of Ávila (1515–1582), the mystic and Carmelite reformer, used metaphorical images of fire, water, candle, and wax to describe the soul’s union with God. Author Mirabai Starr writes:

The Beloved (as you teach us, Saint Teresa) longs for union with us as fervently as we long for union with him. God’s desire for the soul is no less than the soul’s desire for God. It is a matter of perfect reciprocity (you assure us). Believe it.

The only difference is that when the soul unites with the Holy One, she disappears and he grows. She is the raindrop falling into the river. He is the river calling her home. She is the candle flame burning in the daytime. He is the sun absorbing her. They are a single sea. They are one fire. [2]

Since my Beloved is for me and I for my Beloved, who will be able to separate and extinguish two fires so enkindled? It would amount to laboring in vain, for the two fires have become one. [3]

| The Suffering Servants of Today |