The Hero’s Journey

Richard Rohr uses the framework of the “hero’s journey” to describe the path of spiritual transformation. He points to The Odyssey as a powerful metaphor:

The universe story and the human story are a play of forces rational and nonrational, conscious and unconscious, involving fate and fortune, nature and nurture. Forces of good and evil play out their tragedies and their graces—leading us to catastrophes, backtracking, mutations, transgressions, regroupings, enmities, failures, mistakes, and impossible dilemmas. The Greek word for tragedy means “goat story.” The Odyssey is a primal goat story, where poor Odysseus keeps going forward and backward, up and down—but mostly down—all the way home to Ithaca. [1]

The hero’s journey is a key myth that keeps repeating in different cultures. I learned about it from mythologist Joseph Campbell. The hero or heroine—the gender really doesn’t matter—must leave home or business as usual. They have to leave what feels like sufficiency or enoughness. There is a sense of necessity in discovering the bigger world. We’ve got to know there’s a bigger world than my home state of Kansas, or wherever we’re from. In The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy has to leave Kansas—and she’s taken away by a tornado. We usually don’t leave home willingly. More often than not, we’re taken there by some circumstance, shipwreck, accident, death, or suffering of some sort. That’s called theDEPARTURE The hero has to lose or walk away from their sense of order and enter some kind of disorder.

Then there’s the ENCOUNTER. After the hero leaves their castle or their stable home, they have to experience something bigger, something better, something that is more real and more demanding of their real energies. Of course, that takes different forms. In the Gospels, after his baptism, Jesus goes into the desert for forty days.

Surprisingly, the third stage of the hero’s journey is the RETURN. The hero’s journey is not to just keep going to new places, making the trip a vacation or travelogue. We have to return to where we started and know it in a new way and do life in a new way. We are not somehow “beyond” the order and disorder of our lives; we’ve learned how to integrate both of them. This stage of return is so rarely taught. What is good about the order, what is good about the disorder, and how do we put them together? That is the “reorder” or the return.

We have the departure, then we have the encounter, which will always lead to some kind of descent away from status, away from security, away from ascent. Eventually something happens, something gets transformed, and then there’s the return. [2]

Falling Down and Moving Up

Father Richard identifies the heroic journey as a type of “falling upward” into a new way of being:

A down-and-then-up perspective doesn’t fit into our Western philosophy of progress, nor into our desire for upward mobility, nor into our religious notions of perfection or holiness. “Let’s hope it is not true, at least for me,” we all say. Yet the Perennial Tradition, sometimes called the wisdom tradition, says it is and will always be true. St. Augustine called it the passing-over mystery (or the “paschal mystery,” from the Hebrew word for Passover, Pesach).

Today we might use a variety of metaphors: reversing engines, a change in game plan, a falling off the very wagon that we constructed. No one would choose such upheaval consciously. We must somehow “fall” into it. Those who are too carefully engineering their own superiority systems will usually not allow it at all. It is much more done to us than anything we do ourselves, and sometimes nonreligious people are more open to this change in strategy than are religious folks who have their private salvation project all worked out. This is how I interpret Jesus’ enigmatic words, “The children of this world are wiser in their ways than the children of light” (Luke 16:8). I’ve met too many rigid and angry Christians and clergy to deny this sad truth, but it seems to be true in all religions until and unless they lead persons to the actual journey of spiritual transformation.

Falling down and moving up is the most counter-intuitive message in most of the world’s religions, including Christianity. We grow spiritually much more by doing it wrong than by doing it right. That just might be the central message of how spiritual growth happens, yet nothing in us wants to believe it. I actually think it’s the only workable meaning of any remaining notion of “original sin.” There seems to have been a fly in the ointment from the beginning, but the key is recognizing and dealing with the fly rather than throwing out the whole ointment!

By denying their pain and avoiding the necessary falling, many have kept themselves from their own spiritual journeys and depths—and therefore have been kept from their own spiritual heights. Because none of us desire, seek, or even suspect a downward path to growth, we have to get the message with the authority of a “divine revelation.” So, Jesus makes it into a central axiom: The “last” really do have a head start in moving toward “first,” and those who spend too much time trying to be “first” will never get there (Matthew 19:30). Jesus says this clearly in several places and in numerous parables, although those of us still on the first journey just cannot hear this. It has been considered mere religious fluff, as much of Western history has made rather clear. Our resistance to the message is so great that it could be called outright denial, even among sincere Christians.

====================

| Sorrowful Yet Always Rejoicing |

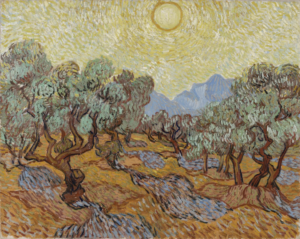

Van Gogh’s painting of olive trees was intended to represent Jesus’ suffering in Gethsemane. He gave the trees a vaguely human form in order to “make people think” more than if he had depicted Jesus explicitly. Another noticeable difference from traditional depictions of Gethsemane is the brightness of Vincent’s painting. He did not paint the shadows of a garden at night, which would fit what the gospel writers tell us. Instead, his garden of olive trees is under a blazing golden sun. Like so many of his paintings, this one is dominated by yellow, van Gogh’s color for divine love. The trees writhing in pain appear to be stretching upward toward the infinite joy of God.The simultaneous mixing of joy and sorrow is a common theme in Vincent’s paintings and in his life. He said, “It is true that I am often in the greatest misery, but still there is a calm pure harmony and music inside me.” This paradox should be familiar to anyone who belongs to Christ. The Apostle Paul described himself as a common jar of clay that nonetheless contained a priceless treasure. He said he is afflicted, perplexed, persecuted, and wasting away—and yet, he saw these momentary troubles as nothing compared to the eternal glory that awaits him. Later, he described himself as “sorrowful yet always rejoicing” (2 Corinthians 6:10). This paradox captured van Gogh’s imagination as a young man. In 1876, he preached an English sermon on the topic. He said:“Sorrow is better than joy…for by the sadness of the countenance, the heart is made better. Our nature is sorrowful, but for those who have learnt and are learning to look at Jesus Christ, there is always reason to rejoice. It is a good word, that of St. Paul: as being sorrowful yet always rejoicing. For those who believe in Jesus Christ, there is no death or sorrow that is not mixed with hope—no despair—there is only a constant being born again, a constantly going from darkness into light.”Perhaps this explains why he painted his version of Gethsemane in bright sunlight. The terrible suffering of Jesus in the garden was not the full story. Through his suffering, there would also be resurrection, new birth, the defeat of evil, and the reconciliation of all things to God. This is what Vincent tried to capture with his painting. The contorted olive trees reaching up to the sun represent Jesus’ journey and ours from darkness to light. There is pain, but there is also hope. There is sorrow, but there is also joy. Good Friday contains the mystery of our faith. The cross is a paradox we are invited to embrace even as we fail to comprehend it. It is a moment of unimaginable sorrow and pain; of injustice and cruelty. It represents, as Jesus said when he was arrested, the “hour when darkness reigns” (Luke 22:53). And yet, it is simultaneously the moment when darkness is defeated, when injustice is disarmed, and when our sorrow turns to joy. In these uncertain times, when there is so much fear and suffering, the cross reminds us as van Gogh preached, “there is no death or sorrow that is not mixed with hope. ”DAILY SCRIPTURE ISAIAH 61:1-4 2 CORINTHIANS 4:7-18 MARK 15:33-39 WEEKLY PRAYER From Bernard of Clairvaux (1090 – 1153) You taught us, Lord, that the greatest love a man can show is to lay down his life for his friends. But your love was greater still, because you laid down your life for your enemies. It was while we were still enemies that you reconciled us to yourself by your death. What other love has ever been, or could ever be, like yours? You suffered unjustly for the sake of the unjust. You died at the hands of sinners for the sake of the sinful. You became a slave to tyrants, to set the oppressed free. Amen. The post Sorrowful Yet Always Rejoicing first appeared on With God Daily. |