Being Peaceful Change

Love

at the Center

Friday, July 31, 2020

Blessed are the peacemakers: they shall be recognized as children of God. —Matthew 5:9

Today many think we can achieve peace through violence. The myth that violence solves problems is part of the way we think and is in direct opposition to all great religious teachings. Our need for immediate control leads us to disconnect the consistency, connection, and unity between means and ends. We even named a missile created for the destruction of humanity a “peacekeeper.” But such peace is a false peace, the Pax Romana of mutually assured destruction (MAD). We must wait and work for the Pax Christi of mutually assured forgiveness.

The above verse from Matthew is the only time the word “peacemakers” is used in the whole Bible. A peacemaker literally is the “one who reconciles quarrels.” Jesus is clearly not on the side of the violent but on the side of the nonviolent. Jesus is saying there is no way to peace other than peacemaking itself.

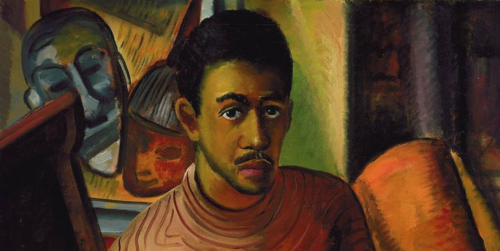

Coretta Scott King reflects on her husband Martin Luther King, Jr.’s commitment to nonviolence with love at its center:

Noncooperation and nonviolent resistance were means of stirring and awakening moral truths in one’s opponents, of evoking the humanity which, Martin believed, existed in each of us. The means, therefore, had to be consistent with the ends. And the end, as Martin conceived it, was greater than any of its parts, greater than any single issue. “The end is redemption and reconciliation,” he believed. . . .

Even the most intractable evils of our world—the triple evils of poverty, racism, and war which Martin so eloquently challenged in his Nobel lecture—can only be eliminated by nonviolent means. And the wellspring for the eradication of even these most economically, politically, and socially entrenched evils is the moral imperative of love. In his 1967 address to the anti-war group Clergy and Laity Concerned, he said:

When I speak of love I am not speaking of some sentimental and weak response. I am speaking of that force which all of the great religions have seen as the supreme unifying principle of life. Love is somehow the key that unlocks the door which leads to ultimate reality. This Hindu-Moslem-Christian-Jewish-Buddhist belief about ultimate reality is beautifully summed up in the first epistle of Saint John: “Let us love one another; for love is God and everyone that loveth is born of God and knoweth God” [1 John 4:7].

If love is the eternal religious principle, Martin Luther King, Jr. believed, then nonviolence is its external worldly counterpart. He wrote:

At the center of nonviolence stands the principle of love. The nonviolent resister would contend that in the struggle for human dignity, the oppressed people of the world must not succumb to the temptation of becoming bitter or indulging in hate campaigns. To retaliate in kind would do nothing but intensify the existence of hate in the universe. Along the way of life, someone must have sense enough and morality enough to cut off the chain of hate. This can only be done by projecting the ethic of love to the center of our lives. [1]