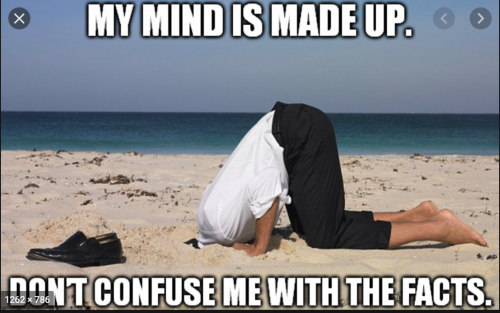

Learning how to see our biases is a psychological exercise, but one with immediate theological and social implications. It demands self-knowledge and the crucial need to recognize (1) when we are in denial about our own shadow and capacity for illusion; (2) our capacity to project our own fears and shadows onto other people and groups; (3) our capacity to face and carry our own issues; and (4) the social, institutional, and political implications of not doing this work.

If some Christians think that this is mere psychology, then they surely need to know that Jesus himself was a consummate analyst of human nature. He was really a brilliant psychologist and named many of the issues that we call today “denial,” “bias,” “projection,” and “the shadow self.” He also emphasized the necessity of inner healing of hurts to avoid continuing to hurt others.

Brian McLaren offers this perspective on why Jesus’ teachings were so effective in freeing people from an over-attachment to their own way of seeing:

When you aggressively attack people’s familiar ideas, they tend to respond defensively. They dig in their heels and become even more firmly attached to the very ideas that they need to be liberated from. . . .

That’s why Jesus, like other effective communicators, constantly told stories, stories that grabbed people by the imagination and transported them into another imaginative world:

. . . there once was a woman who put some yeast into a huge batch of dough [Matthew 13:33]

. . . there once was a man who had two sons [Luke 15:11]

. . . this man was traveling from Jerusalem to Jericho [Luke 10:30]

. . . a woman once lost a coin [Luke 15:8] . . .

Through these short “imaginative vacations” to another world, Jesus helped people see from a new vantage point. He used imagination to punch a tiny hole in their walls of confirmation bias, and through that tiny hole, some new light could stream in and let them know of a bigger world beyond their walls. . . .

[Jesus] didn’t spend a lot of time repeating or refuting the false statements of his critics, and he didn’t counterpunch when he was attacked or insulted, but instead, he used every criticism as an opportunity to restate, clarify, and illustrate his true statements. He had, to use a contemporary phrase, message discipline, which drew people to his central simple message: an invitation to overcome long-held biases, to think again, and to see and live life in a new light. [1]

It’s so hard to be vulnerable, to say to our neighbor, “I don’t know everything” or to say to our soul, “I don’t know anything at all.” Yet Jesus says the only people who can recognize and be ready for what he’s talking about are the ones who come with the mind and heart of a child (see Matthew 18:3). The older we get, the more we’ve been disappointed and betrayed by life and others, the more barriers we put up to what Zen masters call “beginner’s mind.” We must never presume that we see “all” or accurately. We must always be ready to see anew.